What is a dish you grew up with?

I grew up in South East London, around Peckham and Bermondsey and my dad was a real South London boy. But he ended up working in restaurant design for places like Conran, so he was exposed to all these different fancy restaurants, bringing home interesting dishes to a family that normally ate pie and mash and fish and chips.

“[My dad] would cook farfalle pasta, mix it with a tin of tuna, raw pepper and raw onion then wonder why I would sit there f****** crying at the dinner table.”

My dad, like my mum, loved Italian food. We joke about him being the person who had the biggest influence on me becoming a cook, but that definitely isn’t true. I think I still have PTSD about pasta because of him. Especially pasta salad. He would cook farfalle pasta, mix it with a tin of tuna, raw pepper and raw onion then wonder why I would sit there f****** crying at the dinner table. It almost felt masochistic. Same with Bolognese, we’d eat it all the time. It spurred me on to buy my own cookbooks and try different cuisines. So maybe he was a big influence…

The food I loved were the humble, hearty dishes. Steak and kidney pie – any pie really. Sausage and mash, fish and chips. They will remain my death row meals.

I was fortunate enough to be raised by my grandparents as well as my parents. And even more fortunate to have grandparents that cooked a lot. They introduced me to offal and made things like black pudding sandwiches, which as a curious kid, I loved. My grandma made amazing sausage rolls. She was the only person I know who made them with shortcut pastry and that were f****** delicious. She passed away many years ago now, and I remember trying to replicate them to invoke those childhood memories but they just didn’t taste the same.

The pastry was very firm when it came out; not too buttery like you get from puff. I think she would have used lard for some or all of the fat. And the pork sausage itself would have been really simple. You know, good, cheap, simple meat.

Another dish I loved was my mom’s stuffed lambs’ hearts. It was a very, very simple dish but I can still taste them. The mix was made from breadcrumbs, onions, garlic and herbs. The hearts would go in a tray or pot, on top of a mirepoix. She’d add some stock, not covering the hearts entirely, and cover with a lid, so the steam would prevent the top from drying out. The hearts would then braise on a slow cook. The braising liquid was delicious and the heart would be very delicate. You could slide through them with a blunt knife.

It wasn’t gastronomic in any way but it was simple, tasty cooking.

What is the first recipe you remember following?

I grew up wanting to be a musician. I mean, I still am a musician, but I had dreams of being in a rock band touring the world. So school wasn’t something I had any interest in whatsoever.

There was a turning point in my life when I was around 20. It was life-changing. I won’t go into detail but suffice to say that my dreams of being a professional musician were crushed for a while, and I was in limbo of not quite knowing where to go, or what to do.

“The acidity from the mustard popping through, the layers of the herbs, the little pops of capers. It all just dances on your palette.”

A friend got me a job in a pizza restaurant in my hometown and I bounced around kitchens for a couple of years. I still didn’t want to be a chef at that point, but always thought ‘I’m better than this place’. That’s until I ended up at The Swan.

It was the first place that made me think I could be a chef, that it was a meaningful profession. Before then I had been cooking pre-portioned fish, using bad ingredients, not really engaging. But at The Swan I really began to understand the importance of ingredients. We’d do weekly runs to Billingsgate and Smithfield markets, doing proper butchery and fish prep. It was captivating and a real eye opener for me.

A recipe that sticks out at that time in my career was green sauce. It wasn’t anything too complicated, but it was something we made gallons of. And I loved it.

We’d start with a massive bunch of parsley, along with a bunch of mint, half of tarragon, basil and dill. There would be a healthy spoon of Dijon mustard in there, a good quality red wine or sherry vinegar, olive oil, anchovies and super fine capers. I remember capers being a revelation. Biting into those little, perfectly round bursts of saltiness. Those would always be mixed in right at the end.

I still love eating steaks with that green sauce. Don’t get me wrong, Béarnaise sauce with chips and steak is a different level of happiness, but if you have a rolled ribeye, cut into thick slices and cooked on the grill until the fat is charred and melting, you want something punchy. The acidity from the mustard popping through, the layers of the herbs, the little pops of capers. It all just dances on your palette.

As well as serving it with steaks, we’d use it to marinade racks of lamb, or take a spoon of it to finish a lamb sauce. It really showed its versatility. Fergus at St John has this little ode to green sauce, explaining how by chopping or blending it in different ways it gives you very different uses. So when keeping the ingredients relatively coarse, for example, it’s almost like a salad.

What is the recipe you’ve made the most?

Béarnaise stands out as something I’ve made so much of. I’ve made it so many times I could do it blindfolded. Vats of the stuff. I’ve teetered on the edge of failure so many times, but I’ve developed a great technique for bringing them back. I kind of pride myself on being able to step in and help someone with a split sauce.

The way I cook is the way I like to eat. I love rich, umami packed dishes, but also having things to balance them out. With a Béarnaise or Hollandaise sauce, we’re already on our way to a rich unctuous flavor profile. I loved adding anchovies and confit garlic into them. I know it’s a fairly common thing to do now but I remember thinking how delicious it was to have this beautiful salty emulsion and then a pop of sweet garlic coming through.

Now I take the sauce another step and add seaweed or wakame. That sauce of course lends itself to red meat, but adding a little dusting of powdered dulse or fine shreds of seaweed makes it work beautifully with any grilled fish or lamb.

These ingredients can go in at the beginning or the end but if you know where you’re going with the sauce, putting them in earlier in the process is going to give you a better depth. Like if you’re using tarragon, you could use a tarragon infused vinegar to make your sabayon. So if we know we’re going to be putting anchovies and garlic in, you can definitely put some in at the beginning, even using some of that tinned anchovy oil as part of the emulsifying process.

In terms of bringing back a split sauce, it’s all in the small detail. You can’t rush the process. You put a few drops of ice water down the side of the bowl, then whisk very gently, gradually making the circles bigger and bigger and bigger. Some people put ice water in there and then they whisk and whisk and whisk and it’s not coming back, and they’re wondering why. You have to make sure you start small and be patient. After a while you’ll start to see it come back together.

Who are the cooks or chefs whose recipes have inspired you?

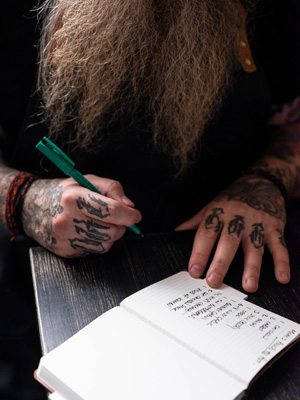

I was only about a year or so into my career when someone handed me Kitchen Confidential. This was around 25 years ago and kitchens were very different then. You had the military style discipline, and beards and tattoos weren’t common like they are now. So for someone like me, who didn’t have that discipline, who wanted to be a musician, Bourdain’s rock and roll attitude reassured me that there were other people out there like me.

When I went to The Swan and I started to learn about a good type of discipline, the first book they gave me was the French Laundry. The head chef at the time would take excerpts out of the book, print them and put them on the wall or in our recipe book. This tuned me into the respect of ingredients and pushing towards new levels of excellence.

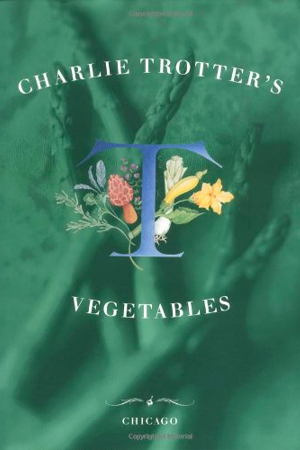

But it was Charlie Trotter who probably had the biggest influence on me. I had his cookbooks quite early, when I first started working in a kitchen. It wasn’t the way he cooked so much, but the type of ingredients he would use. I remember thinking ‘wow, this is what a real chef is’. He would have all these different ingredients on a plate and I wanted to understand what they were. Ingredients that are on everyone’s radar now but 20 years ago were totally new to people. Things like goose barnacles and quinoa. Obviously quinoa has become a bit of a victim of health food, but at the time it was such an interesting and unique ingredient.

But it was Charlie Trotter who probably had the biggest influence on me. I had his cookbooks quite early, when I first started working in a kitchen. It wasn’t the way he cooked so much, but the type of ingredients he would use. I remember thinking ‘wow, this is what a real chef is’. He would have all these different ingredients on a plate and I wanted to understand what they were. Ingredients that are on everyone’s radar now but 20 years ago were totally new to people. Things like goose barnacles and quinoa. Obviously quinoa has become a bit of a victim of health food, but at the time it was such an interesting and unique ingredient.

Charlie Trotter’s books were also very visual, which I loved. Instagram has become so influential in cooking over the past decade because a lot of chefs work in colors and visuals, so in a time before this, cookbooks like Charlie’s would allow me to explore new dishes through the images… much more so than words.

What is the recipe you would hand down to your family?

My mom was a great cook. When I was a kid I didn’t appreciate this. In my teenage years, I thought her cooking was good. By my twenties I would go back to see her as much as I could because I missed the cooking. She sadly passed away recently and I think part of her legacy will be her food.

It’s funny, whenever I go for dinner somewhere people get worried that they’re cooking for a chef. But my mum had none of that. She didn’t care if her son was a chef. She was going to cook what she wanted to cook, and love what she was doing. And there’s an honesty and beauty to that.

There’s a handful of her recipes that I still continue to cook, as part of her legacy. A lot of them are quite classic, like Tartiflette and Poule Au Pot.

Her Poule Au Pot was something we’d eat as much as twice a week. A whole chicken would go in a pot filled with water and simmered with the usual suspects; carrots, celery, garlic and a bundle of bay, rosemary and thyme. But the rest of the ingredients would vary seasonally. In the summer it might be hispi cabbage and some butter beans, and in the winter you’d have savoy cabbage, pearl barley and other grains or lentils. She would sometimes thicken it up with a little bit of peas dumping, but whatever she added, whatever the season, she would always include dumplings.

These dumplings were just beautiful and light. They’d be made with two parts self raising flour and one part suet, or some kind of shortening, plus water or milk to bind. She’d season and maybe add in some Dijon mustard and soft herbs. The dumplings would boil at the bottom of the pot then be pushed to the top to get a nice crispy top on the oven.

My mum was fond of dishes from around the world, but when it came to Poule Au Pot she didn’t want any ingredients that weren’t native to Europe. I would sometimes experiment with the dish, like maybe a sheet of kombu in the braise or adding guajillo and ancho chilis to give the dish warmth, but my mum wouldn’t have any of that.

When my mum passed it was the first thing we cooked as a family. We were going through a period of grief and there was nothing more comforting than that dish. It’s like a hug in a bowl.

What is a dish on your current menu that represents your approach to cooking?

It’s a roasted leek dish which comes with a pistachio romesco sauce. When you think of the old Catalonian romesco dish, it’s a real classic. They have celebrations and festivals about this dish. So we know that when we grill these alliums on the embers, they’re gonna taste great.

They’re black on the outside and they steam in the middle. We can’t get calçots, which they use, all year round, but we can get leeks and they’re a great alternative. You char them up on the outside, letting them steam in their own juices, and then peel away that blackened outer layer. Then you have this beautifully soft, creamy leek inside. It lends itself to nutty things.

It’s not cheap, using pistachios, but it’s delicious. They would replace almonds and instead of red peppers, we would use green peppers, and we would put green chili in there, all roasted on the fire beforehand. So again you get that nice depth of flavor, the smokiness, the sweetness. Because we had such an abundance of leeks – and there’s only so many kinds of leek oils you can make – but we would use a leek oil in the romesco as well. So you get this really nice pop of color and that allium flavor popping through. I would say you can’t come to Acme and not have the leeks and green romesco.

We’ve changed the plating of the dish a few times. Unfortunately pistachios have gone through the roof, as have a lot of the ingredients in this dish. So we’ve changed it from when we used to put a nice pile of leeks tenderly on top of a generous pile of romesco. We’ve had to do it the other way around, where we dress the leek with some romesco. We were faced with either taking the dish off the menu because we can’t afford to have it on, or to change the way we do it. So it’s more about the leeks and less about the romesco now, but there was probably a little too much in the past. Either way, it’s a good thing to do at home. It is very simple.

We’ve changed the plating of the dish a few times. Unfortunately pistachios have gone through the roof, as have a lot of the ingredients in this dish. So we’ve changed it from when we used to put a nice pile of leeks tenderly on top of a generous pile of romesco. We’ve had to do it the other way around, where we dress the leek with some romesco. We were faced with either taking the dish off the menu because we can’t afford to have it on, or to change the way we do it. So it’s more about the leeks and less about the romesco now, but there was probably a little too much in the past. Either way, it’s a good thing to do at home. It is very simple.

You could throw grilled chicken or something into the mix and have that grilled chicken, onions, leeks and greens from Mexico, that would work. I’d like to think it’s a very satisfying dish. The reason we haven’t taken it off the menu is that the guests love it and they talk about it, and I think if anything represents my cooking and Acme’s cooking, it’s the fact that we try to cook everything over fire. We make sure that all the leek tops are reused into oil, kimchis and all sorts of other stuff that we make out of the leek tops. We do way more zero waste cooking but this is a start. When we cook the leeks, quite often it’s at the end of service so we never waste fuel. When we’re cleaning down at the end of the night, if there are still embers, they can still cook. So we can get prep on for the next day while we’re cleaning.

Adriana Cavita

LONDON, UK

"I need to balance traditional preparation with modern techniques. I can use traditional recipes as the basis of my creations, but I must also tap into my imagination and passion to create something new and unique."

Chetan Sharma

LONDON, UK

"For any young British Asian chef, or any chef interested in Indian cooking, I want them to be able to come into this restaurant and understand Indian food and Indian flavors, but also learn techniques and be open minded."

Rafael Cagali

LONDON / SAO PAULO

"Opening Da Terra was a reconnection to my own origins. I felt lost in a way. The name Da Terra means from the earth, the idea being not to forget what you come from. I like to think that I’m still exploring Brazilian cooking."

Chris Leach

LONDON, UK

"There are quite a lot of recipes I’m proud of, but there are a few that I feel are genuinely original to me. My pig skin ragu recipe is one of those. There is no meat, or rather, flesh, in the dish; it's made from just pig’s skin."